US Connected TV Advertising 2020

A Surging Channel in an Uncertain Year

Executive Summary

Because viewers continue to flock to streaming video, connected TV (CTV) ad spending will continue to increase for the foreseeable future. Even in the midst of a global recession, CTV will be a bright spot in the ad industry this year.

How much will US advertisers spend on CTV?

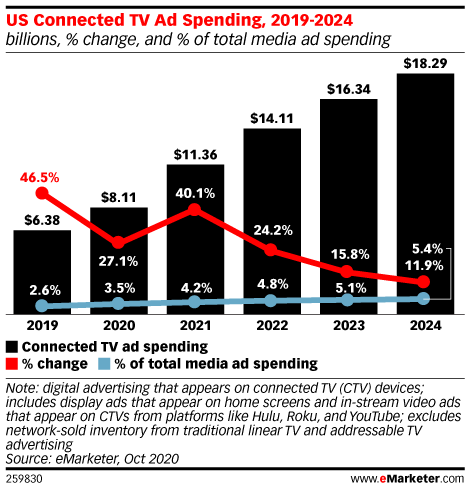

In 2020, US CTV ad spending will total $8.11 billion and will increase to $11.36 billion in 2021. By 2024 it will reach $18.29 billion, more than double the amount spent this year.

Which companies will receive the most CTV ad dollars?

Net revenues from YouTube, Hulu, and Roku collectively account for about half of all CTV ad revenues.

Who is viewing content through CTVs?

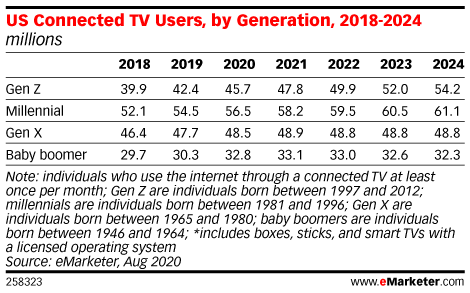

Younger audiences are more likely to be CTV viewers, but older demographics are catching up. US CTV viewers in 2020 will total 45.7 million for Gen Z; 56.5 million for millennials; 48.5 million for Gen X; and 32.8 million for baby boomers.

What are the biggest challenges advertisers have with CTV?

Measurement, ad fraud, and planning campaigns in fragmented markets remain chief CTV advertising challenges.

WHAT’S IN THIS REPORT? This report presents our US CTV ad spending forecast and discusses the challenges advertisers face with this medium.

KEY STAT: US CTV ad spending will increase 27.1% to $8.11 billion in 2020.

Behind the Numbers

Our CTV advertising forecast includes digital advertising that appears on connected TV devices, including display ads that appear on home screens as well as in-stream video ads that appear on CTVs from platforms like Hulu, Roku, and YouTube. It excludes network-sold inventory from traditional linear TV and addressable TV advertising. Estimates are based on the analysis of various elements related to the ad spending market, including macro-level economic conditions; historical trends of the advertising market; historical trends of each medium in relation to other media; reported revenues from major ad publishers; estimates from other research firms; data from benchmark sources; consumer media consumption trends; consumer device usage trends; and eMarketer interviews with executives at ad agencies, brands, media publishers, and other industry leaders.

Glossary

Addressable TV: Targeted TV ads delivered on a home-by-home basis via cable, satellite, and telco boxes. It includes both linear and video-on-demand (VOD) delivered in this way but excludes CTV, smart TV, and OTT.

Ad-supported VOD (AVOD): These services include free platforms like YouTube as well as those, like Hulu, that charge a subscription fee in addition to serving ads.

Advanced TV: Television paired with technology that allows for new features, components, or uses. Addressable TV, programmatic TV, and OTT are all subsets of advanced TV.

Automatic content recognition (ACR): Technology that tracks what people watch on internet-enabled TVs. Marketers use this data to measure which programs and ads viewers see.

Connected TV (CTV): A TV set connected to the internet through built-in capabilities or through another device such as a Blu-ray player, game console, or set-top box (e.g., Apple TV, Google Chromecast, Roku).

Cord-cutter: Someone who once had but then canceled a pay TV service.

Cord-never: Someone who never subscribed to pay TV in the first place.

Cord-trimmer: Someone who cut back on their pay TV service level but still subscribes.

Esports: Organized gaming competitions among professional players and teams.

Linear TV: Television programming distributed through cable, satellite, or broadcast networks; includes VOD.

Multichannel video programming distributor (MVPD): A service provider that delivers programming over cable, satellite, or wireline or wireless networks.

Over-the-top (OTT): Any app or website that provides streaming video content over the internet and bypasses traditional distribution; examples include HBO Max, Hulu, Netflix, and YouTube. Traditional distribution includes internet protocol TV (IPTV), cable, satellite, wireless carriers and fiber operators, multiple system operators (MSOs), MVPDs, and major TV broadcast and cable networks.

Pay TV: A service that requires a subscription to a traditional pay TV provider; excludes IPTV and pure-play digital video services (e.g., Hulu, Netflix, YouTube, Sling TV, etc.). Traditional pay TV providers include cable, satellite, telco and fiber operators, MSOs, MVPDs, and major TV broadcast and cable networks.

Programmatic: Ads transacted via an application program interface (API), including everything from publisher-erected APIs to more standardized real-time bidding (RTB) technology.

Programmatic TV: The use of software platforms to automate the buying or selling of TV advertising distributed through cable, satellite, or broadcast networks.

Smart TV: A TV with built-in internet capability.

Subscription video-on-demand (SVOD): These services generate revenues through selling subscriptions to consumers. Examples include Netflix, Disney+, and Amazon Prime Video.

TV Everywhere (TVE): A streaming service operated by a TV, cable, or satellite network—or by an MVPD—that requires users to authenticate their pay TV subscriptions in order to access the content.

Upfront: Digital video ad spending committed in advance, including spending resulting from the TV upfront events, the Interactive Advertising Bureau (IAB) Digital Content NewFronts, and other meetings throughout the year.

Virtual multichannel video programming distributor (vMVPD): An MVPD that delivers its service via the internet; interchangeable with “linear OTT.” Examples include Sling TV and YouTube TV.

CTV Advertising and User Trends

Streaming video was already steadily gaining viewers coming into 2020. Then an economic recession drove more people to discontinue paying for traditional TV and turn to cheaper streaming options to fulfill their entertainment desires. Meanwhile, widespread quarantines led to a bump in the amount of time people spend with digital video. The increase in CTV usage attracted money from advertisers.

CTV Ad Spending

When we published our inaugural CTV ad spending forecasting last year, we said that $8.88 billion would be spent on CTV ads in 2020 and that figure would rise to $14.12 billion by 2023. The pandemic led us to adjust those numbers.

In our updated forecast, we lowered our 2020 CTV ad spending estimate to $8.11 billion. We decreased CTV’s ad spending growth for this year because the pandemic forced advertisers to significantly reduce their planned spending.

But even with a lowered growth rate, US CTV ad spending will still witness a 27.1% year-over-year (YoY) increase in 2020. This is a much greater increase than seen in other digital channels. For comparison, total US digital ad spending will increase 7.5% this year.

The future for CTV is bright. We increased our forecast for CTV ad spending in upcoming years. In 2023, we forecast that CTV ad spending will reach $16.34 billion, and by 2024 it will reach $18.29 billion, more than double the amount spent this year. In our previous forecast, we expected 2023 CTV ad spending to total $14.12 billion.

We raised our CTV ad spending outlook because the pandemic made streaming video a more regular habit for many people. The pandemic reduced people’s disposable income, which contributed to a record year in cord-cutting, with a 7.5% decrease in traditional pay TV households this year.

With many folks stuck at home, cheaper streaming services became their main video entertainment. This year, on average, the amount of time that US adults spend watching subscription OTT video will increase 23.0%. People are now spending an average of more than an hour (62.3 minutes) per day watching subscription OTT, and most of that viewing happens on TV sets.

Whenever the advertising sector recovers from our current recession, companies selling CTV ad inventory stand to benefit. In fact, some are already reaping rewards from these changes in viewing patterns.

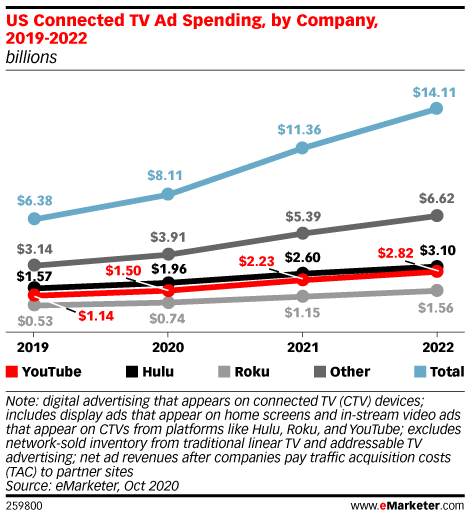

For the first time, we broke out CTV ad revenues for YouTube, Roku, and Hulu. On a gross basis, YouTube will be the largest US CTV ad seller this year with $2.89 billion in gross CTV ad revenues. On a net basis, YouTube will make $1.50 billion in CTV ad revenues in 2020. (The gap between our gross and net ad revenue estimates for YouTube reflect YouTube’s content acquisition costs. Traditional TV networks, multichannel networks, influencers, digital publishers, and others can release their videos on YouTube, then take a cut of the resulting ad revenues.)

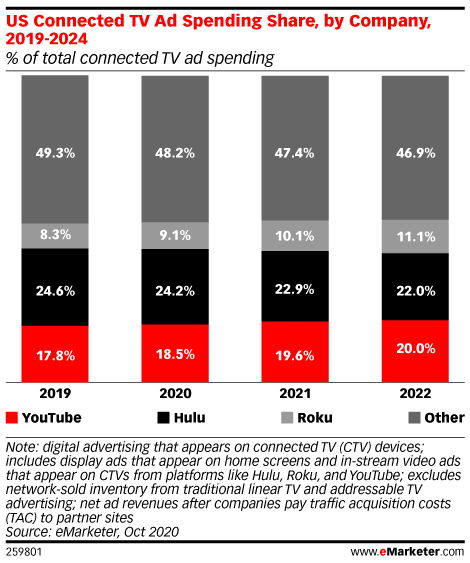

YouTube’s net CTV ad revenues will account for 18.5% of total US CTV ad spending in 2020.

Hulu’s net CTV ad revenues will total $1.96 billion in 2020. That figure will grow to $3.10 billion in 2022. Hulu will account for just under one-fourth (24.2%) of total US CTV ad spending this year. Hulu’s share of net US CTV ad spending will remain larger than that of either YouTube or Roku through 2022, the end of our forecast period. However, we expect Hulu’s share to decline over that timeframe, while both YouTube and Roku will capture larger slices of CTV ad outlays over the next few years.

Roku’s net CTV ad revenues will increase from $740 million this year to $1.56 billion in 2022. This year, just 9.1% of CTV ad spending will go to Roku.

Net CTV ad revenues from YouTube, Hulu, and Roku represent about half of all US CTV ad revenues. Of the remaining half, a large chunk likely goes to Amazon, which sells CTV inventory that appears on its Fire TV operating system as well as its IMDb TV streaming service. While Fire TV has fewer users than Roku does, Amazon can monetize its users more effectively by leveraging shopper/retail data that advertisers crave, said Dave Morgan, founder and CEO of TV targeting company Simulmedia.

Other companies with significant CTV advertising revenue streams include TV makers such as Samsung and Vizio; TV networks such as NBCUniversal, WarnerMedia, and ViacomCBS; and publishers who partner with YouTube, Hulu, and Roku. There is overlap between these categories because a single piece of content can easily appear across numerous platforms.

Overlapping CTV Ad Revenues

To appreciate how complicated the CTV ecosystem is, consider all the ways that a person can view a single show such as “Saturday Night Live.” Clips or full episodes of “SNL” can be seen on YouTube, Hulu, and Peacock, in addition to NBC’s linear TV channels and its TV Everywhere offshoots. These apps are available across mobile, desktop, tablet, and smart TV devices such as Roku. Due to all the viewing options available, it’s possible for this one show to bring viewership and ad revenues to numerous companies including NBC, YouTube, Roku, and Hulu.

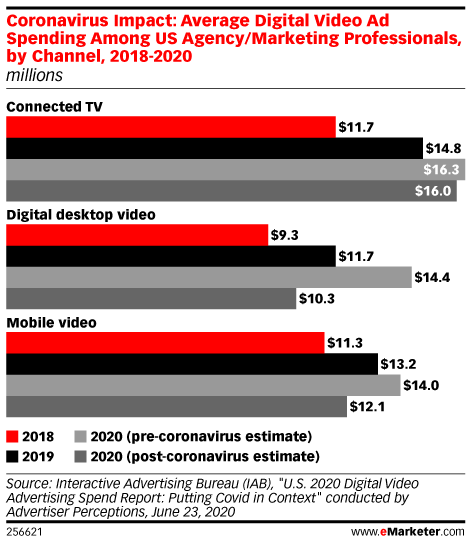

The pandemic hasn’t dampened advertisers’ enthusiasm for CTV. In a June 2020 poll of marketers conducted by IAB, 59% of respondents said they would increase their CTV and OTT ad spending in H2 2020 compared with the same time period a year ago. Just 18% planned to decrease their CTV and OTT ad spending.

Marketers also planned to increase their CTV and OTT budgets by 25% YoY in Q3 and by 27% YoY in Q4, according to the IAB survey.

On average, US agency and marketing professionals planned to spend $16.0 million on CTV this year, up from $14.8 million last year, per IAB and Advertiser Perceptions data published in June. Pre-pandemic, marketers had planned to spend $16.3 million on CTV. So, planned CTV budgets came down some in the wake of the pandemic, but not much.

Since the pandemic, these budgets are being allocated within a tighter window. Pre-pandemic, marketers planned their CTV campaigns between four and five months in advance, according to an April 2020 poll by Advertiser Perceptions. Once the pandemic struck, CTV campaigns were planned between two and three months in advance. As witnessed across other marketing channels, the length of preparation leading up to CTV campaigns got cut in half due to the marketplace uncertainty.

Short planning windows are also common in political ad campaigns where marketers require flexibility as they try to efficiently unload their budgets before Election Day. In recent months, political ad spending increased amid the buildup to the election, and CTV absorbed some of those dollars.

Between April and September, CTV political ad spending at supply-side platform (SSP) SpotX increased ninefold. These increases are common to what happens at local TV companies during election years, where the bulk of political ad spending is concentrated in the last eight weeks before the election.

At demand-side platform (DSP) Centro, CTV accounted for 25% of the programmatic political ad dollars that went through its system between January 1 and October 5, 2020. In 2018, just 5% of Centro’s programmatic political ad spending happened via CTV.

Bloomberg reported that demand for political advertising on YouTube was so strong that in the weeks leading up to the election, YouTube struggled to place all the political ads that were purchased through its platform.

Shorter campaign planning also makes programmatic buying more attractive. We forecast that about six in 10 CTV ad dollars will transact programmatically this year, up from four in 10 in 2018. By 2022, about two-thirds of CTV ad dollars will transact programmatically. Our programmatic CTV figures are influenced by YouTube’s heavy reliance on automation. In other words, without YouTube, the share of CTV advertising transacted programmatically would decrease a fair amount.

Ad buyers we spoke with said they purchase CTV programmatically through private marketplaces (PMPs) and programmatic direct deals. Speaking on the record, ad buyers pooh-poohed open exchanges. And while top-tier streaming apps often restrict their inventory from being sold on the open market, a fair amount of CTV inventory is still sold on open exchanges because many video publishers and advertisers are constantly trying to reach targeted audiences cheaply, said Raghu Kodige, co-founder and chief product officer of TV measurement company Alphonso.

Although most programmatic CTV buying happens outside open markets, there is still more activity within open CTV exchanges than what some advertisers acknowledge.

As of October, private programmatic deals accounted for three-fourths of CTV impressions served by SpotX this year. The remaining ones went through the open market. And in a September survey of 150 OTT ad sellers in the US, conducted by Forrester and SSP PubMatic, respondents said they expected the amount of OTT ad revenues resulting from sales through open programmatic exchanges to increase over the next 12 months.

A downside of open markets is that they can increase exposure to fraud. In a later section, we’ll cover the problems with open markets, along with research that suggests that brands are suffering from CTV fraud schemes.

What Isn’t Considered Connected TV?

CTV is in a unique position: It’s literally the connection between television and digital. As such, many firms have slightly different definitions for CTV advertising, some including facets of both worlds.

To reiterate, our definition focuses solely on digitally delivered ads to TV sets, be it via their own internal internet capabilities or external capabilities delivered by streaming devices, Blu-ray players, and gaming consoles. These ads are primarily video, but we also include digital display ads shown on TV sets.

So, what don’t we consider CTV? CTV does not include any ads delivered to computers, phones, tablets, or other non-TV devices, and it does not include any network- or broadcaster-sold inventory from traditional linear TV or addressable TV advertising. That means we exclude most social video ad spending because it largely comes from outstream mobile ads.

But does it include OTT? It may—if that video is streamed onto a TV set. We define OTT as video that’s delivered independently of a traditional pay TV service, regardless of device. CTV refers specifically to video watched on a TV set with internet connectivity.

A word of caution for this report: Because industry insiders and data providers often use the term “OTT” to refer to services that are geared primarily toward CTV viewing, we will use the term OTT when it is deployed by interview subjects and data sources.

CTV Usage

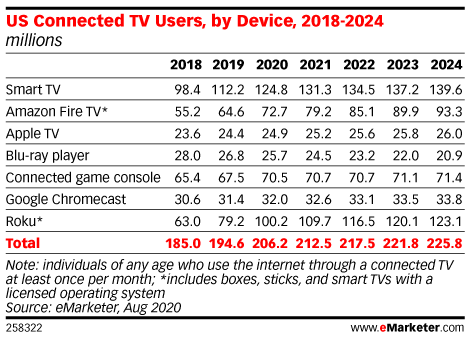

CTV will reach four-fifths of US households this year. With 206.2 million people viewing CTV content, the channel is no longer a marginal one for marketers. Internet-enabled smart TVs are the most common device, with 124.8 million US users expected to watch content through smart TVs this year.

When broken out by operating system, Roku and Amazon Fire TV are the most popular CTV products. Roku will have 100.2 million users, and Fire TV will have 72.7 million.

It’s worth calling out that people can use multiple devices, and it isn’t unusual for a single household to have multiple TVs in their home or to use both a Roku and Fire TV. There is also overlap in our smart TV figures. A smart TV user is someone who uses the built-in features on their TV to access content via the internet. But our smart TV estimates have overlap because Roku, Amazon, and Google license their operating systems to numerous smart TV manufacturers. This means that our estimates for Roku and Fire TV users include their separately sold streaming sticks, as well as the viewers they reach through smart TVs that use their operating systems.

We expect smart TVs, Roku, and Fire TV to continue their strong user growth this year but to essentially plateau by the end of our forecast period. Roku and Fire TV have gained users by selling devices cheaply at a low profit margin and earning their revenues by monetizing those devices through advertising. The usage of other CTV devices like Apple TV and Google’s Chromecast will stay relatively flat.

Younger audiences are more likely to be CTV viewers, but older demographics will add more viewers in 2020. This year, we broke out CTV viewers by generation for the first time. US CTV viewers in 2020 will total 45.7 million for Gen Z; 56.5 million for millennials; 48.5 million for Gen X; and 32.8 million for boomers. Compared with the same figures a year ago, Gen Z viewers increased by 7.7%; millennials by 3.5%; Gen X by 1.8%; and boomers by 8.3%.

The number of boomers who watch content through CTVs is still significantly fewer compared with younger cohorts, but boomer adoption of streaming video has increased. Nearly half of boomers, 46.1%, will use CTV in 2020, up from 40.9% in 2018. This year, more than three-fourths, 77.5%, of millennials will use CTV, which makes that generation the most likely generation to use the channel. By 2024, usage of CTV by Gen Z, millennial, and Gen X viewers will be similar, with about four-fifths of their total populations using CTV at least once per month. Slightly less than half of boomers will use CTV by 2024.

As more people turn to CTV, controlling their streaming interface has become a high-stakes game. Device makers, streaming apps, and content producers each want a piece of the ad inventory, ad revenues, and user data that are associated with streaming. HBO Max and NBCUniversal’s Peacock aren’t available on Fire TV due to disagreements over inventory and content sharing. HBO Max also isn’t available on Roku. Because this field has become more lucrative, Comcast and Samsung are also trying to license their operating systems to TV makers.

CTV Challenges

Advertisers and viewers are excited by CTV, but the channel isn’t without its growing pains. Confusion over who controls budgets, who has access to given inventory, how to manage measurement, and how to avoid ad fraud are common pain points.

Controlling CTV Budgets

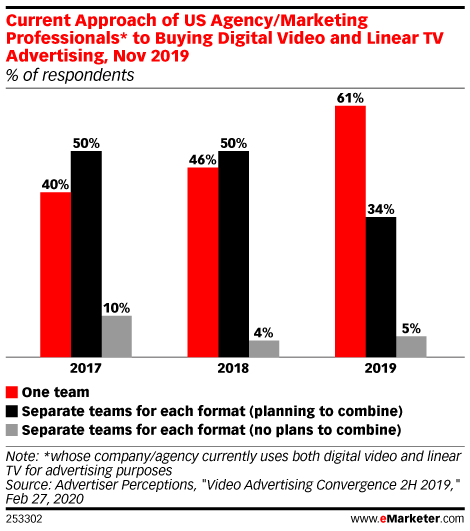

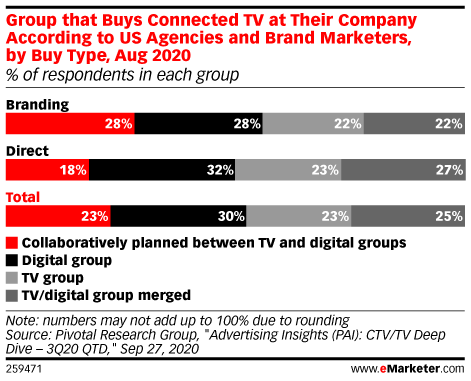

The departments responsible for CTV planning and buying vary across brands and agencies. For some advertisers, these responsibilities are handled by the linear TV team. At other companies, the digital team handles them. Some advertisers have merged their TV and digital video teams into a single video group. Separate video and TV teams are becoming rarer, but some advertisers still utilize that approach.

In 2019, 61% of agency and marketing professionals had one combined team handle their digital video and TV buying, up from 40% in 2017, according to Advertiser Perceptions. One-third of respondents had separate teams for digital video and TV but were planning to combine them. Just 5% had no plans to combine.

Pivotal Research Group found less convergence in its August 2020 survey of US agencies and brand marketers. About one-third of its 50 respondents said their digital group handles CTV buying, and 23% said CTV buying was controlled by their TV group. Just one-quarter said their TV and digital groups had merged. Another 23% said their TV and digital groups collaborate when planning CTV campaigns.

“There’s a lot of politics that continue to happen at the agency level,” said Kelly McMahon, senior vice president of global operations at SpotX. “There is becoming more of an assertion in terms of who is controlling CTV budgets. … I’m seeing more and more dollars being controlled by the linear teams, especially because CTV is becoming a bigger part of the upfront negotiation process.”

This year, the confusion surrounding the upfronts increased scatter market demand for CTV inventory, according to Simulmedia’s Morgan. Because scatter inventory is more expensive than upfront inventory, it became difficult for advertisers to lock in CTV inventory at a low price.

“Some of the TV network groups said, ‘Hey, we don’t need to throw our CTV stuff into upfront packages unless we get a real premium for it because there’s such a demand,’” Morgan said.

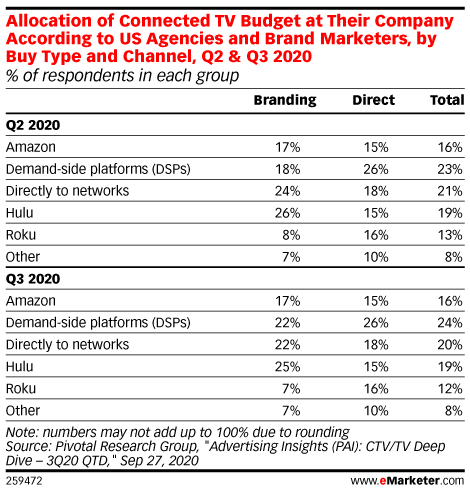

The way CTV budgets are allocated differs between branding and direct-response advertisers, according to Pivotal’s marketer poll. For direct-response advertisers, buying programmatically through a DSP was a common way to spend CTV ad dollars in Q2 and Q3 2020. Branding advertisers were more apt to buy directly from TV networks or digital publishers like Hulu.

Accessing Inventory

When buying CTV inventory, advertisers have the option to buy from multiple sources, such as streaming device manufacturers, makers of smart TVs, content aggregators, programmatic ad exchanges, digital video publishers, and broadcast networks. This means the inventory is spread out in a way that makes it hard for any single channel, or provider, to deliver the kind of scale that advertisers are accustomed to with linear TV.

Figuring out who has the ability to sell specific inventory can be a daunting task. Amazon, Roku, and Samsung each control a free ad-supported app (IMDb TV, The Roku Channel, and Samsung TV Plus) where they sell inventory. They also sell a portion of the inventory on other ad-supported apps that viewers access through their platforms. But the share of inventory they can sell varies by app, and they don’t have the ability to sell every app’s inventory.

Amazon, Roku, Samsung, and Hulu each declined to comment on which companies they have inventory selling agreements with. A Google spokesperson confirmed that YouTube inventory is either sold by Google or by publisher and creator partners who sell a portion of the inventory for their own YouTube channels. This means that device operators don’t sell YouTube inventory.

In interviews for this report, there was confusion over who could sell Hulu inventory. A few advertisers said that Hulu inventory couldn’t be bought from Roku or Fire TV. Others said that Hulu could be purchased in small amounts from Roku or Fire TV. Trade publication Digiday reported that Hulu doesn’t allow Roku to sell its inventory.

This distinction may come down to semantics. An advertiser shared lists with us from Roku and Amazon that showed which ad-supported apps they partnered with. Hulu was included in each list, while YouTube was not.

Catherine Dettloff, vice president of media at ad agency Marketing Architects, said that advertisers can’t isolate inventory from Hulu, or any other publisher, when buying through Roku. But advertisers buying through Roku can still have some of their ads land within Hulu because the streaming platform is a Roku partner. Roku doesn’t provide reporting at the app level for apps it doesn’t own and operate. But Roku provides more granular details, such as which programs ads ran against, for ads that appear within The Roku Channel, according to Dettloff.

“They’ll give you a report that tells you what categories of apps you spend in, but they won’t tell you what apps they monetized,” said Jesse Math, OTT lead at ad agency Tinuiti.

Another way to access some Hulu and YouTube inventory is by working with publishers who have shows on those apps. NBCU’s ad sales team can sell inventory that appears against its shows on external platforms such as YouTube, Hulu, and Snapchat, according to Mike Reidy, senior vice president of digital ad sales at NBCU. Reidy didn’t specify which Hulu inventory NBCU has access to sell, but MediaPost reported that Hulu’s TV network partners can sell inventory on Hulu for a show’s most current season.

YouTube allows partners to sell inventory that appears within their own YouTube channels. Generally, YouTube takes a 45% cut of the ad revenues, while the content owners receive 55%.

When advertisers buy YouTube inventory from publisher partners, they have greater control to make sure their ads are placed within specific shows, said Geoff Schiller, chief revenue officer of Group Nine Media, which sells YouTube inventory across its media brands that include PopSugar, Thrillist, and The Dodo.

When advertisers buy YouTube inventory through Google, their ads may run across hundreds of channels within a single genre. Making a single buy through Google—as opposed to setting up dozens or hundreds of buys across individual publishers—may be easier, but the trade-off is precision over where ads get placed. For brands that fear getting called out for having an ad appear next to unsavory content, precision can be as important as scale.

Measurement and Fraud

Changes in how consumers view video content have made audience and advertising measurement more difficult. And without consistent definitions and standards across different systems, it can be difficult to simultaneously buy and measure the same audiences across disparate platforms.

More than half of US marketers polled by Advertiser Perceptions in November 2019 cited a lack of standard measurement as a leading challenge to cross-screen video advertising. Nearly six in 10 marketers said that when they added OTT to their linear buys, they purchased impressions without knowing their reach, frequency, or effectiveness.

Why do marketers keep investing in a channel where they receive unclear reporting? It’s because streaming video’s massive viewership gains, especially among young people, make the channel unavoidable. In Advertiser Perception’s study, 69% of marketers reported that they don’t mind advertising on a video platform they don’t understand as long as it provides results.

Since the pandemic led to drawback of ad spending, advertisers have adjusted their CTV campaign goals, said Kavita Vazirani, executive vice president of insights and measurement at NBCU. “There is a heightened desire to maximize every dollar that’s spent and really focusing in on more of the business impact and the business outcomes vs. the perceptual KPIs [key performance indicators] of just lifting awareness and consideration.”

Marketers should be strict about their KPIs, keep measurements simple where possible, harmonize data from different sources, and make incremental improvements instead of trying to tackle everything at once. But even when following those guidelines, measuring CTV advertising is particularly challenging because ad buyers have the option to buy from many inventory sources.

Integrating campaign reports from streaming device manufacturers, makers of smart TVs, content aggregators, programmatic ad exchanges, and broadcast networks takes work. Making sure the ad exposure and ad impact measurements are consistent across these services requires expertise.

Advertisers would like smart TV makers, streaming device manufacturers, streaming services, and measurement vendors to share more data so that advertisers can strengthen their measurements. More data sharing could theoretically lead to more consistent measures across platforms. But these platforms won’t likely open their data anytime soon. Business interests—in particular, the goal of maintaining a competitive advantage—disincentivize sharing any information that could possibly give competitors any inkling as to what’s really going on. There are also data privacy concerns about pooling together data to satisfice advertisers.

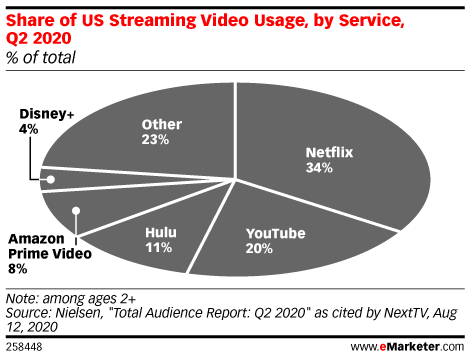

Another challenge in measuring CTV audiences is that most of the time people spend streaming happens devoid of advertising. The ad-free services Netflix, Prime Video, and Disney+ accounted for nearly half of all time spent with streaming in Q2 2020, according to an August 2020 Nielsen report. The two most popular services with advertising, YouTube and Hulu, feature subscription ad-free tiers, so a portion of viewing on those platforms also happens without ads. The top five streamers accounted for about three-fourths of all time spent with streaming.

The long tail that makes up the remaining fourth is split between ad-free services (like Apple TV+), ad-reliant services (like Pluto TV), and hybrid services that have ad-supported and ad-free tiers (like Peacock). When added together, there is a massive amount of streaming happening without ads, which is how many users like it. Users have repeatedly cited Netflix’s lack of ads as one of its most attractive features.

Marketers can still reach viewers of ad-free services with workarounds. Tactics marketers use to reach viewers of ad-free services include striking product placement deals, using automatic content recognition (ACR) data to spot when audiences flip to ad-supported platforms; buying ads on affiliated properties; and utilizing lookalike modeling and contextual targeting to try to comply with privacy laws.

But these tactics have trade-offs and require work. Marketers can layer them onto a media plan, but they can’t fully replacement advertising directly on a premier video platform.

An additional problem with CTV advertising is that the growing number of ad dollars spent on CTV has attracted fraudsters. Between January and April 2020, ad fraud detection company DoubleVerify detected a 161% YoY increase in fraudulent CTV ad impressions. Last year, Pixalate, another firm that monitors ad fraud, estimated that 22% of programmatic OTT and CTV ad impressions were served as invalid traffic. Vendors in this area have unveiled numerous CTV fraud schemes that they claim were worth millions of dollars.

Some sources interviewed for this report viewed CTV ad fraud studies with skepticism.

“With some of these companies, those stats are skewed toward what makes the problem sound bigger than it probably is in actuality,” said Andre Swanston, co-founder and CEO of data management platform Tru Optik. “They’re definitely skewing toward the open exchange stuff. … A lot of those stats are misleading and exaggerated.”

And according to Math of Tinuiti: “A lot of the [CTV ad fraud] percentages that are out there are self-serving marketing percentages.”

In an October 2020 post titled “Fearmongering in CTV Advertising,” Comscore stated that it detected a CTV post-bid invalid traffic rate that was slightly higher than 1%. The article advised ad buyers to “separate marketing talking points from fact” when analyzing CTV ad fraud.

Other sources we spoke with believed CTV ad fraud was common. “There is a lot of manufactured inventory,” Simulmedia’s Morgan said. “CTV is showing a really high fraud rate.”

Charles Cantu, founder and CEO of ad tech company Reset Digital, said the biggest issue with CTV advertising is that “people have been hoodwinked for so long thinking they can get cheaper CPMs,” which leads advertisers to end up wasting money on fraudulent inventory.

Ad fraud rates are highest on open marketplaces, but fraud can happen within PMPs too, according to John Ross, associate director of CTV products at DoubleVerify. “Anyone can kind of setup a PMP,” Ross said. “It doesn’t necessarily require a real-life relationship between two companies.”

According to Ross, it isn’t unusual for so-called premium CTV publishers to use extension networks. Sometimes, most of the ads publishers sell don’t run on their owned and operated properties. Instead, the ads run across a network of lower-quality apps. Audience extensions, which have been common for web publishers seeking to boost their display ad sales and perceived traffic numbers, haven’t died out.

When extension networks’ contributions to ad campaigns are clearly spelled out and made transparent, they can be potentially useful to advertisers who want more inventory than the publisher they’re working with has to offer. However, audience networks also can lead to mislabeled inventory, and when the inventory isn’t sold transparently, they can contribute to fraud.

Key Takeaways

- Compared with other advertising channels, CTV is having a great year. CTV ad spending will increase 27.1% to $8.11 billion this year. Advertiser investment in CTV is increasing because viewers are increasingly leaving traditional TV, and CTV offers ad buyers flexibility.

- Younger people are more likely to be CTV viewers, but CTV is catching on with older demographics. US CTV viewers in 2020 will total 45.7 million for Gen Z; 56.5 million for millennials; 48.5 million for Gen X; and 32.8 million for boomers. Streaming is becoming more common among older demographics as the recession reduces disposable income and people look for cheap entertainment options.

- YouTube, Hulu, and Roku account for about half of total CTV ad revenues. These companies have stood out in the CTV advertising market due to their large user bases and access to bulk inventory. In upcoming years, Amazon, TV manufacturers, and TV networks will bring greater competition for CTV ad dollars.

- CTV is rife with challenges. Issues such as audience measurement, ad fraud, and market fragmentation give advertisers headaches. For now, this emerging and growing space lacks widely accepted standards, which adds difficulty to managing cross-screen video campaigns.